How Ice, Motion, and Engineering Power the Games

I am so excited for the 2026 Winter Olympics to start this week! Every Winter Olympics feels a little magical in our house. My family has a watch party for every Games, complete with our favorite tradition of trying to recreate foods from the host region and cheering as athletes from all over the world come together to celebrate sport, culture, and community. Growing up in Colorado, I’ve spent my life on snowy slopes (both skiing and snowboarding) and also took figure skating lessons for many years as a child, so winter sports have always felt close to my heart. I’m especially excited to watch fellow Colorado athletes compete in Milan this year.

But beyond the excitement, the medals, and bringing together of countries across the world, what I love most about the Olympics is how naturally they invite curiosity. Every race, jump, spin, and slide becomes a chance to notice the science behind the movement, and that makes the Winter Olympics one of my favorite real-world classrooms.

The Winter Olympics: A Real-World Science Lab

The Winter Olympics serve as a perfect real-world science laboratory. Every glide, spin, and high-speed turn depends on a combination of physics, materials science, and human biology working together. In this Winter edition of The Science of Sports, we’ll explore what makes ice so slippery and how different winter sports turn that unusual surface into speed, control, and precision.

Newton’s Laws of Motion in Winter Sports

Newton’s laws of motion explain nearly every movement in the Winter Olympics. Newton’s first law of physics, which describes inertia, can be observed across every sport. When a skier drops into a downhill run or a bobsled leaves the start gate or a hockey puck skids across the ice, the athlete and their equipment naturally keep moving unless a force such as friction, air resistance, or a turn changes that motion.

Newton’s second law demonstrates how much an athlete speeds up, slows down, or changes direction depending on how strong the forces are acting on them. Bigger forces cause bigger changes in motion. A stronger push with a skate, a steeper hill, or a sharper turn all create a bigger change in speed or direction. Every time a skier presses an edge into the snow, a skater pushes against the ice, or an athlete plants a pole, they are changing the forces on their body, and those changing forces are what make them speed up, slow down, or turn.

Newton’s third law is often explained as “every action has an equal and opposite reaction.” This means that whenever an athlete pushes on something, that surface pushes back just as hard. When a figure skater presses down and backward into the ice to jump, the ice pushes upward and forward on the skater. That push from the ice is what actually lifts the skater into the air. Silmilarly, when a snowboarder pushes against the wall of a halfpipe, the wall pushes back on the board and sends the rider upward. Athletes do not jump or launch themselves by pushing on the air; they move because solid surfaces push back on them, and that reaction force is what makes takeoff possible.

Together, these three laws explain how winter athletes start moving, speed up, slow down, turn, and fly.

The Biology of Cold-Weather Performance

Winter athletes must contend with not just competition, but the elements. Cold air and altitude affect muscle function, oxygen delivery, and even energy metabolism. Training regimes are tailored to improve cardiovascular efficiency, muscle power, and the ability to perform at peak levels despite these challenges.

For biathlon competitors, mastering the switch between intense skiing and precision marksmanship requires both physical control and mental discipline which is an extraordinary example of how physiology and psychology intersect in sport.

Snowmaking, Weather, and Climate Science

While we often think of snow as a natural backdrop, many Olympic venues rely heavily on artificial snow production, especially as global temperatures warm. Snowmaking involves pumping super-cooled water and compressed air through specialized nozzles in a blend of thermodynamics and fluid mechanics to create snow when nature doesn’t cooperate.

Climate science plays an even bigger role: warming trends are shrinking reliable snow seasons in many traditional winter sport regions, raising questions about the future of winter competitions and how athletes and organizers adapt. I am witnessing this first hand here in Colorado where our normally snowy ski slopes are relying heavily on artificial snow this year. At the same time, many regions of the USA are getting snow when historically they never do. This demonstrates how Global Warming is a misnomer and is better characterized as Climate Change instead.

Why Is Ice So Slippery?

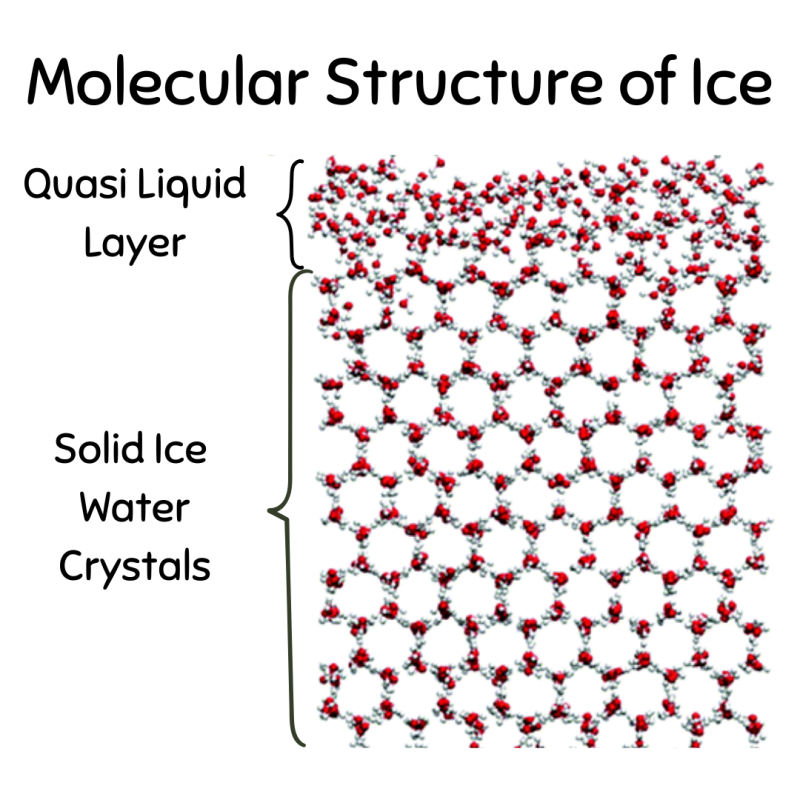

Ice is slippery because its surface behaves differently than most solid materials. Scientists have discovered that the very top layer of ice is covered by an extremely thin film of water that is only a few nanometers thick—thinner than a strand of hair—and this is often called a quasi-liquid layer. Remarkably, this layer exists even when the ice is below freezing.

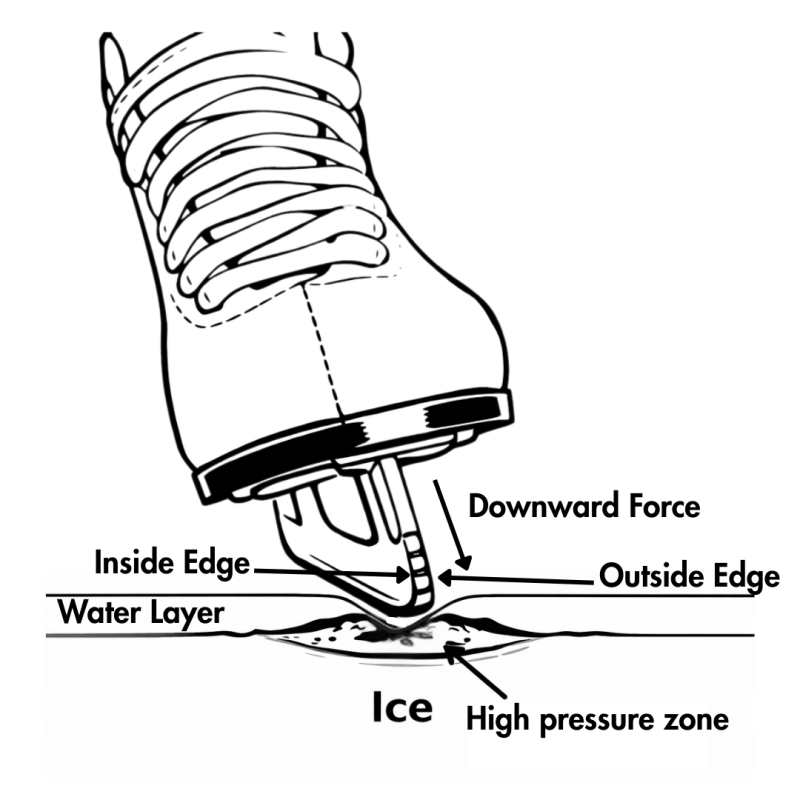

The water molecules at the surface are not locked into a rigid crystal the way they are deeper inside the ice. Instead, they remain loosely connected and can move more easily, creating a soft, mobile “skin” on top of the ice. When a skate blade, sled runner, hockey puck, or curling stone slides across the surface, this layer rearranges quickly and acts as a natural lubricant. Pressure and friction can make the layer slightly thicker, but the key idea is that the ice surface is already different from the solid ice underneath it.

This microscopic layer is one of the main reasons ice allows athletes to move with such low friction in sports like skating, curling, hockey, and bobsled.

Skating Science: Friction, Rotation, and the Human Body

Speed skating and figure skating both rely heavily on the special physics of ice, but they use it in very different ways.

In speed skating, thin steel blades glide on the ice’s quasi-liquid surface layer, allowing extremely low friction. At the same time, skaters must generate enough grip to control direction in corners. Modern blades are carefully engineered for hardness, thickness, and shape, and many skaters use hinged clap skates that allow the blade to remain in contact with the ice longer during each push. This improves force transfer and efficiency.

Biomechanics plays a major role. Skaters hold deep crouched positions and generate powerful sideways pushes. Researchers study joint angles, muscle activation, and balance to understand how athletes convert muscular force into forward motion while remaining stable on blades only millimeters wide.

Figure skating highlights rotational physics and human movement science. When a skater pulls their arms inward during a spin or jump, their rotation speed increases due to conservation of angular momentum. During takeoff, large forces are produced in a very short time by the hips, knees, and ankles. Landing is equally scientific: by bending at the knee and hip, skaters increase the time over which they stop, reducing stress on the body. Balance depends on the brain’s motor control systems, vision, and the inner ear working together to keep skaters oriented during rapid spins and mid-air rotations.

Hockey: Collisions, Energy, and Rapid Control

Ice hockey combines friction physics, materials science, and human reaction science. Players constantly switch between low-friction gliding and high-friction stopping and turning by changing how the blade contacts the ice. Sharp edges dig into the surface to generate large sideways forces for fast cuts and explosive stops.

The puck itself is designed to slide rather than bounce or roll, making its motion more predictable. Temperature affects how quickly the puck slows down and how it rebounds from the boards. When a puck is colder, the rubber becomes stiffer and harder. A harder puck keeps its shape better as it slides, so it loses less energy to bending and wobbling. That usually means a cold puck slides faster and more predictably across the ice. This is why professional games often use pucks that are kept chilled before play.

When a puck is warmer, the rubber becomes softer and slightly squishier. As it slides, a soft puck deforms more where it touches the ice. That extra deformation increases energy loss, so the puck tends to slow down a little faster and may feel less “clean” when passing or shooting.

During a slap shot, the hockey stick bends before striking the puck. This stores elastic energy in the composite material, which is then released into the puck, increasing its speed. Hockey also showcases the physics of collisions. Protective equipment and flexible boards increase the time over which players slow down during impacts, reducing peak forces on the body.

Curling: Surface Science and Controlled Friction

Curling is a quiet but powerful demonstration of surface physics. Each granite stone touches the ice only along a narrow circular ridge called the running band. The ice itself is covered with tiny frozen droplets known as pebble, which greatly reduce contact area and allow the heavy stone to glide.

When players add a small rotation at release, the stone slowly spins as it moves forward. Tiny differences in friction between the front and back of the stone, combined with the textured ice surface, create a small sideways force that causes the stone to curve near the end of its path.

Sweeping does not simply melt a puddle of water. Instead, sweeping slightly warms and smooths the tops of the ice pebbles, reducing friction ahead of the stone. This allows the stone to travel farther and straighter before the curling effect becomes dominant.

Skiing: Gravity, Glide, and Turning Forces

Skiing is driven by gravity converting height into speed. As skis move across snow, pressure and friction create a thin lubricating water layer that helps reduce resistance and improve glide. At the same time, air resistance acts to slow the skier, especially at higher speeds.

Turning requires carefully controlling edge angle, body rotation, and pressure. Skiers manage their center of mass relative to the skis while counteracting the outward force felt during a turn. Modern shaped skis make it easier to control these forces, allowing athletes to carve smoother and more stable turns.

Engineering the Winter Sports Environment

Engineering plays a major role in winter sports, from the design of skis, snowboards, skates, and hockey pads, to the construction of entire competition venues. Equipment is engineered with specific shapes and materials so athletes can control friction, edge grip, and energy transfer. Venues such as skating rinks require engineering specific temperatures so that the ice is perfectly formed while halfpipes and terrain features on the slopes use precise geometry to balance lift, speed, and safety.

Some of the most complex engineering achievements are the bobsled and luge tracks, where the total drop, curve shapes, banking angles, and refrigeration systems are carefully designed to control speed, manage sideways forces, and maintain consistent ice conditions. The bobsled itself is also a precision machine, built with lightweight composite shells, vibration-absorbing frames, and finely tuned steel runners that must balance low friction with reliable grip. Because mass and layout are tightly regulated, engineers carefully position components to create a stable center of mass, allowing the sled to respond smoothly and predictably at high speeds.

Why the Science of Winter Sports Matters

From microscopic water layers on ice to large-scale engineering of tracks and equipment, the Winter Olympics reveal how science shapes performance at every level. These sports make concepts such as friction, force, rotation, surface structure, and human biomechanics visible in ways students can observe, discuss, and test for themselves.

For families and classrooms, winter sports are a powerful reminder that science is not limited to labs and textbooks, but it is embedded in movement, design, and even the slow curve of a curling stone across the ice.

Add comment

Comments